Grave of the Fireflies Explained: Hidden Japanese Meanings You Missed

September 6, 2025

- Grave of the Fireflies Review|Introduction

- Not Just Anti-War: Okada’s Radical Interpretation

- The “Shinjū” Reading: Setsuko and Seita’s Silent Pact

- Beyond Little Sister: Setsuko as Idealized Woman

- The Watermelon Scene: Visual Minimalism and Guilt

- Seita as the Audience’s Mirror

- Influences of Miyazawa Kenji and Frédéric Back

- Review Summary: Why Grave of the Fireflies Still Hurts

Grave of the Fireflies Review|Introduction

Grave of the Fireflies is a deeply moving animated masterpiece that has left a lasting emotional impact on audiences around the world. Released in 1988 by Studio Ghibli, the film is often labeled as a powerful anti-war statement. However, such a classification barely scratches the surface of what the movie truly represents. As Japanese critic Toshio Okada argues, Grave of the Fireflies is not simply about war—it is a sharp critique of Japanese society, revealing the fate of those who are pushed out of the communal system and left to suffer alone.

This review seeks to go beyond the tears and tragedy. We will explore the film’s philosophical core, rooted in Japanese cultural views on death, familial obligation, and unspoken emotional codes. Using Okada’s interpretation as a starting point, we delve into the psychological layers behind key scenes and character choices. One central question guides our analysis: Why do we feel frustration toward Seita even as we mourn his fate? By the end, you may find yourself rethinking Grave of the Fireflies—not just as a sad story, but as a profound meditation on guilt, responsibility, and the human cost of isolation.

© 1988 Akiyuki Nosaka / Shinchosha, Studio Ghibli

Director: Isao Takahata

Not Just Anti-War: Okada’s Radical Interpretation

While many viewers interpret Grave of the Fireflies as a heart-wrenching anti-war film, Japanese critic Toshio Okada presents a far more radical perspective. He argues that the movie is not primarily about war, but about the failure of society to protect those who fall outside its boundaries. In wartime Japan, survival was often dependent on maintaining one’s place within a family or community. Seita and Setsuko, driven by pride and circumstance, leave that structure—and are ultimately abandoned by it.

According to Okada, their deaths are not simply personal tragedies, but reflections of a larger societal cruelty. The story reveals how Japan, as a collective, discards those who cannot—or choose not to—conform. This interpretation reframes the film as a chilling critique of social systems, not just a lament for wartime suffering. It forces viewers to confront an uncomfortable question: What happens when someone steps outside the safety of the group? In that question lies the film’s most unsettling—and timeless—truth.

The “Shinjū” Reading: Setsuko and Seita’s Silent Pact

In Japanese literature and traditional theater, shinjū—double suicide—represents more than romantic tragedy. It is often a desperate, symbolic escape from a society that offers no space for individual will or freedom. From the plays of Chikamatsu Monzaemon to kabuki classics, shinjū has served as a poignant cultural metaphor. Toshio Okada applies this lens to Grave of the Fireflies, interpreting the story of Seita and Setsuko as a modern, secular shinjū.

Though they are siblings, Seita and Setsuko form a bond that isolates them from the rest of the world. Their connection becomes so absolute that survival outside it is no longer viable. As the outside world turns indifferent or hostile, death becomes a quiet, shared outcome. Seita’s decisions no longer seem rooted in logic or survival, but in a kind of unconscious pact with Setsuko—to follow her wherever she goes, even into death. Within this reading, Grave of the Fireflies is not just about loss, but about a culturally resonant act of mutual disappearance.

127th Bunraku Performance, “Sonezaki Shinjū” – Tenmaya Scene.

Ohatsu: Yoshida Minosuke III

Tokubei: Kiritake Kanjūrō III

Performance Record Photo (YRD0100127500292).

Beyond Little Sister: Setsuko as Idealized Woman

In Grave of the Fireflies, Setsuko is far more than a helpless child. As Toshio Okada observes, she embodies multiple emotional roles in Seita’s mind—she is not only a younger sister, but also a surrogate mother, an imagined wife, and a symbol of emotional sanctuary. One subtle but telling moment shows Setsuko sewing—a task far beyond the ability of a child her age. Rather than literal, this act reflects Seita’s internal projection of a mature, nurturing figure he desperately needs.

Viewed through this lens, Seita’s relationship with Setsuko becomes more psychologically complex. She is the vessel through which he processes his grief, loss, and longing for stability. Instead of clinging to the memory of his actual mother, whose burned corpse he saw, he attaches himself to the idealized purity of Setsuko. The most emotionally charged object in the film is not his mother’s remains, but the tin can containing Setsuko’s ashes. In choosing to preserve that tin, Seita preserves not just her memory—but the illusion of a world where he was not utterly alone.

The Watermelon Scene: Visual Minimalism and Guilt

One of the most haunting scenes in Grave of the Fireflies occurs when Seita brings a watermelon to Setsuko as she lies dying. She takes a single bite—and soon after, quietly passes away. The next cut shows watermelon rinds scattered on the ground, with ants crawling over them. At first glance, it appears the ants have come to feast. But a closer look reveals that the watermelon has been cut into smaller pieces than before, implying that Seita—stricken with hunger—ate most of it after Setsuko’s death.

This subtle visual detail delivers a gut-wrenching contradiction. Seita’s love for his sister was undeniable, yet in the wake of her death, he is still human—driven by hunger, by instinct. However, one piece remains untouched: the very slice Setsuko bit into. Director Isao Takahata resists dramatic flair or overt grief. Instead, with minimalist imagery, he communicates the unbearable mix of sorrow, guilt, and survival instinct. There are no tears, no cries—just silence and a rotting fruit. It is in that silence that the deepest anguish is heard.

© 1988 Akiyuki Nosaka / Shinchosha, Studio Ghibli

Director: Isao Takahata

Seita as the Audience’s Mirror

Many viewers find themselves frustrated with Seita. They ask: Why didn’t he stay with his relatives? Why didn’t he work harder? Why didn’t he beg for help? But this emotional response is not accidental—it is the film’s most deliberate manipulation. Director Isao Takahata places us in a moral position where, in judging Seita, we become part of the very societal rejection that leads to his downfall.

As Okada explains, wartime Japan offered little chance of survival to those who stepped outside the communal order. Seita and Setsuko, by choice or circumstance, became societal outcasts. Their deaths are not simply due to war, but due to the failure of the society around them—and, symbolically, the audience itself. We are not merely watching their suffering; we are complicit in it. The untouched slice of watermelon is not just Seita’s guilt—it is ours. Grave of the Fireflies ultimately holds up a mirror to its viewers, confronting us with our instinct to blame rather than to empathize, to look away rather than act.

Influences of Miyazawa Kenji and Frédéric Back

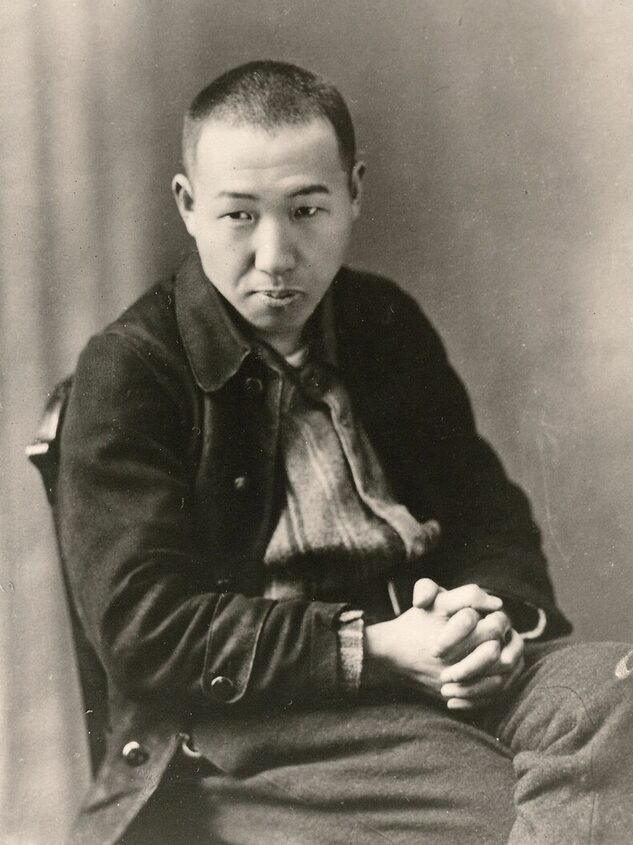

Miyazawa Kenji’s Influence: Death as Guidance

The emotional and artistic depth of Grave of the Fireflies owes much to the quiet influence of two visionary artists: Kenji Miyazawa and Frédéric Back. In Miyazawa’s Night on the Galactic Railroad, death is portrayed not as a finality, but as a spiritual journey—an opportunity for the dead to guide the living from beyond. This concept is echoed in the film’s opening, where Setsuko’s spirit silently watches over Seita, creating a sense of ongoing presence rather than final loss.

or Hanamaki City Museum Collection

Learn more about Kenji Miyazawa (Wikipedia, Japanese) .

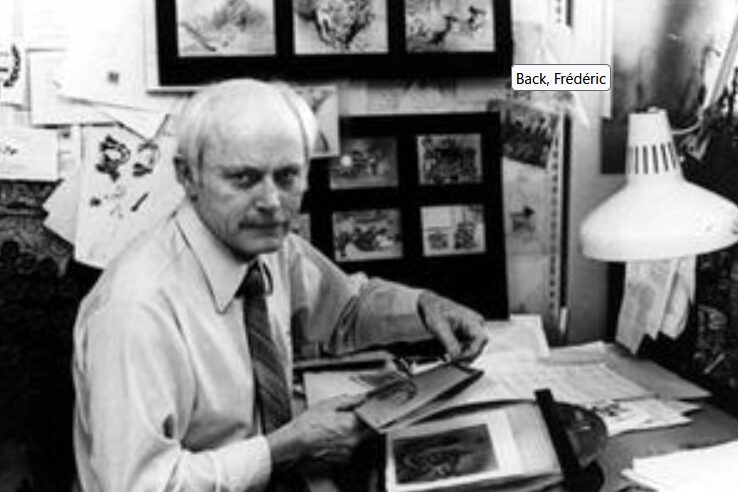

Frédéric Back’s Influence: The Power of What Is Not Said

Frédéric Back, best known for The Man Who Planted Trees, championed visual storytelling that valued silence over explanation. He trusted the audience to feel meaning through imagery alone. Takahata’s own aesthetic mirrors this philosophy. The watermelon scene, the unspoken farewells, the long silences—these are all moments where emotion is conveyed not through words, but through absence. By merging Miyazawa’s spiritual view of death with Back’s poetic minimalism, Takahata crafted a film that is both deeply Japanese and universally resonant.

Canadian animator Frédéric Back, known for The Man Who Planted Trees, shared Takahata’s belief in understatement. Both artists trust silence, imagery, and subtle detail over heavy-handed explanation. The watermelon scene is pure Back: no dialogue, no sentimentality—just an image that speaks volumes, inviting the viewer to notice or to miss it.

For more about his life and works, see Frédéric Back on Wikipedia .

Review Summary: Why Grave of the Fireflies Still Hurts

Grave of the Fireflies is not simply an anti-war film or a tearjerker—it is a mirror held up to society, and to ourselves. What makes it so deeply painful, even decades later, is not just the tragedy of Seita and Setsuko, but how familiar their fate feels. A society that only values those who conform, a system that punishes pride and independence, a bond between siblings distorted by desperation—these are not relics of the past, but living truths that persist today.

Director Isao Takahata’s refusal to dramatize or moralize gives the film its timeless impact. In the quiet, in the shadows, he allows meaning to emerge on its own terms. His style resonates with Kenji Miyazawa’s vision of death as a guide, and Frédéric Back’s devotion to poetic understatement. What remains after the tears is not catharsis, but a question: Would you have helped Seita? That question lingers, haunting and unresolved—and that is why Grave of the Fireflies still hurts.

For official information, please visit the Studio Ghibli official page for Grave of the Fireflies .